Date and sailors unidentified.

1944

OCTOBER

On October 23, 1944 we saw the first Japanese dive-bomber. It dropped its bomb and missed. A few seconds later, it was hit by anti-aircraft and its engines began burning. Seeing that he was going down, he headed for an Landing Craft Infantry (LCI) with a Wildcat right on his tail, but nothing could stop him. He crashed right into the LCI which immediately burst into flame. It burned for about an hour and a half, rolled over and sank.

That gave us an awfully queer feeling. It was the first ship we had ever seen going down and we hoped it was the last.

After that day, it was one raid after another–morning, noon and night. There were certain things that stood out more though.

On the night of the first sea Battle of the Philippines, one of our light carriers was sunk.

(Ralph is referring to the three sea battles of the Battle For Leyte Gulf from October 23 to 27, 1944: Battle Of Surigao Strait, Battle Off Samar, and Battle Off Cape Engano (East Of Luzon).

It was about nine PM when the radio message came in that around twenty-four Wildcats would be landing on the unfinished air strips at Tacloban. At this time we had no land-based planes in the Philippines. The particulars were that we could identify them as they would have their landing lights on. In a short while they began coming in, landing one after another. We were not more than a mile off shore. We could watch everything that was going on.

As the last plane was coming in, he suddenly zoomed up and there was a large explosion in the center of the air strip. Immediately all the guns around opened up on him, and they shot him down back over the island.

That was one of the Japanese. They picked up our message immediately, sent out one of their own planes to follow our own planes in under cover of the darkness to join our planes, turn on her running lights and bomb our air strip that we were trying to build as quickly as we could. I could go on telling these things by the hour, but writing them all down would become very tiresome and lengthy.

NOVEMBER

All through the month of November we continued to unload Liberty Ships and weather out the air raids.

Landing Ship Medium 34.

Date, place and sailors unidentified.

DECEMBER

About the first of December we loaded up with army engineers and equipment and prepared to leave for the invasion of Mindoro, but about then the second sea battle of the Philippines started. This blocked our passage to Mindoro, so we unloaded, and on the third of December prepared for another mission.

The Japanese were reinforcing their troops in Leyte through Ormoc on the other side of the island, so we were to take reinforcements to Bay Bay about forty miles below Ormoc.

The trip around the island was uneventful, but on landing we found that our navigation had been faulty. We had landed about Bay Bay, almost on the Japanese beach.

We landed about one AM and it was very dark that morning on the fifth of December.

The Army told us that we would have to pull off and rebeach at Bay Bay. Our commander told them that either we unloaded there or were taking our loads back to Dulag. We unloaded.

Kamikaze Attacks

About ten AM we were rounding the bottom of the island, and I was sitting topside leisurely watching our small convoy–three destroys, six LCIs and 12 LSMs. There was a spotty covering of clouds and the day was bright and hot. I happened to glance back and saw a plane diving at top speed not five hundred feet above a destroyer. It was Kamikaze. The destroyer never altered course or fired a shot as it all happened too quickly, but the plane exploded in the water, missing its target by at least a hundred feet.

Our GQ (General Quarters) buzzer sounded and then all hell broke loose.

Two planes headed for us almost at the same time.

Our guns got one about fifty feet from the starboard side of our ship.

The second one exploded and crashed a few yards from our bow. Gasoline, water and parts of planes were flying all over the place.

Then a third came in straight for our conn (area of the ship where steering and engine orders are given) from the starboard side. The skipper had stopped, and the Japanese shot in from our conn down over the lifelines on the port side, into the water and exploded. The ship lurched the other way.

This all happened in about five minutes, but it was almost lifetime. The attack continued on furiously. A plane had crashed into the stern of the LSM 20 and she was taking on more water than she could stand. A plane had crashed into the radio shack of the LSM 23, and she was burning from the splattered gasoline.

In about twenty minutes, the 20 began going down stern first. We began picking up survivors s and the planes were still coming in. Our ship picked up three men, two badly burned, and the third unharmed. They were blown off a destroyer by an explosion.

We had several other raids before the day was over. They hit two of the destroyers, one just behind the conn, and flame shot up the ship all the way to the bow. The second, at just about dark, was hit by two bombs midship, and we ended up towing that destroyer for four hours until she got one of her engines fixed.

Upon arriving at Dulag, we loaded again and left again, only this time for the invasion of Ormoc. We went out with twelve LCIs, four APDs (World War I destroyed converted to carry troops and land them, with attack boats that they launch), three destroyers, six LSTs and twelve LSMs. If those aren’t the exact numbers, it is close and to the best of my memory.

The morning of December seventh, we hit Ormoc with little opposition on the beach.

Only a few snipers were there, but while pulling off the beach, a few planes came over and one hit an APDs. It began burning badly. They had to abandon it and our destroyers sank it.

We found out then that when we were pulling in, three Japanese transports and three Japanese destroyers had been coming in. The were only about twenty miles away when we landed, but our planes went out and sank them all that day. We had been just in time.

We pulled out about ten leaving three LSMs and 1 LCI stuck on the beach Two of the LSMs and the LCI came back. The third LSM was sunk that day.

We had plenty of excitement that day, but we had better cover of our own planes. Out of sixty planes that the Japanese sent for us, forty were shot down by our planes, mostly P38’s. They kept coming in the rest of the day. Every twenty to thirty minutes we could expect three or four of them the rest of the afternoon. The sank one destroyer and hit an LSTs with little damage.

However, after those exciting times in such a short number of days, our ship had not been hit. No one was hurt on our ship so they decided we were ready to go on the invasion they had listed us for a week before.

Our fleet had chased the remainder of the Japanese fleet away and our way to Mindoro was clear.

This was a much longer convoy with several cruisers and aircraft carriers along. This was a much longer convoy with several cruisers and aircraft carriers along.

On the way up, two Japanese planes hit the cruiser Nashville. They had one hundred twenty-some killed and over two hundred injured.

Rescue Operations

Nothing else happened until D Day, December fifteenth. When, just as we were pulling off the beach, five Japanese planes came over and hit two LST (Landing Ship Tanks).

They started burning badly. As the LSMs started warming up to pull out, we got a call from the Admiral in charge to pick up survivors from one of the LSTs so we headed for her.

The ammunition on her began going off by then, and it looked like regular fireworks. The tracers shot out in all directions and splashed in the water. There were little streaks of fire all over the where oil and gasoline had poured out. The water was filled with men in life jackets, both Army and Navy.

We opened our bow doors and lowered our ramp and began picking up men from the water and PT boats.

In about an hour, the well deck was full of wet and frightened men.

Just as we began picking up the men, the “T” blew straight up with a huge explosion blowing a big black rolling smoke ring into the air about a thousand feet. It looked as though any men left on the ship when it exploded would be gone. But, I talked with many men afterward that were on her then and were not even bruised.

We picked up about five hundred men, mostly Army. We put all the Army men that could walk off on PT boats, and they were taken ashore as our troops hadn’t even met any Japanese on the beach yet.

We had ten casualties, aboard, nine Army and one Navy. They were all badly burned, and one had a broken back and almost died. We had most of the ship’s crew aboard and some were aboard a destroyer. The Navy men got their heads together, and as far as they could tell, none had been killed. The planes hit midship where she was loaded with eight hundred Air Force ground crew, aviation gasoline and five hundred pound aerial bombs–a hot load.

When we finally left, the convoy had been gone about two hours and we were all alone. It didn’t make us feel so good as we knew there was a continual threat of air attack. One lonely LSM wouldn’t be able to do much about it so we took out at flank speed, cutting all the corners the convoy had taken. The engineers put screw drivers in the governors and held them down. We caught up to the convoy without seeing another planes, and we felt greatly relieved. Our navigator figured we made seventeen knots, as far as I know, it is still the record for LSMs. That thirty-six hundred horsepower did its job.

The trip back to Leyte was quiet, and we were glad to be back. Even though they were still having air raids every day, the planes were more interested in the air strip and the larger ships than us.

We were still in Leyte at Christmastime . Christmas Eve we had a movie in the aft troop compartment. It was the first movie I had seen since we had left Manus. There was an air raid that night, but we did not go to General Quarters (GQ) as the planes were a long way off. We never went to GQ any more unless it looked as though the planes were coming close to us.

Christmas Day was a day we had looked forward to for a long time like a bunch of kids waiting to open their packages. To build up the feeling of surprise, the deck force, the ship’s control and the engineering force had each separately planned a program for entertainment of the rest of the crew. A prize was to be given for the best program. It wasn’t really much, but it was something to keep our minds off the Japanese, if that were really possible.

After a wonderful meal of turkey, sweet potatoes, ice cream, pie, and all the extras such as nuts, celery and cranberry sauce, we put on the program. (I ate so much that I was uncomfortable for the rest of the day). The program was really funny-one of our fellows sang a song that he had made up about the ship, another did a southern shuffle. Between singing songs and imitating our engineering officer going to GQ loaded down with life jacket, two rifles, two forty-fives, a pair of binoculars, and a trench knife, the show was a success.

That night we had the usual air raid.

1945

JANUARY

New Years (1945), we were still in Leyte Gulf, but we were getting restless, and the day was rather dull. Although we had another big meal and the day off, the coming of the New Year didn’t seem much to look forward to. It was just a time to rest and think about the last year and how much longer the war would last.

On January we left on a long, rough and tedious trip to Lingayen Gulf in a large convoy made up mostly of LSTs. Our average speed was from three to five knots. The LSTs were towing LCMs which took a terrible beating. One lost its ramp and had to get underway under its own power and pull out. Another, that had a LCM loaded in her, was swept by a big wave. The LCM, including a truck that was in her, was swept out to sea.

Felix A. Cizewski’s copy of the

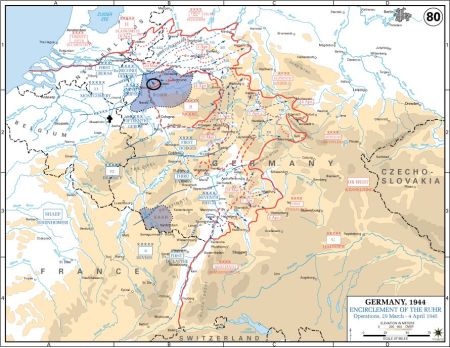

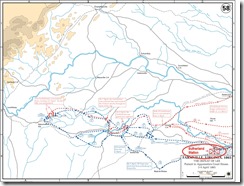

Felix A. Cizewski’s copy of the

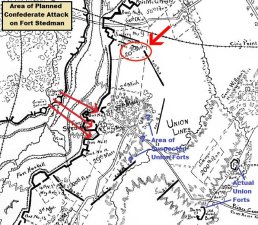

![FortStedmanSidneyKing[1] FortStedmanSidneyKing[1]](https://lhcizewski.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/fortstedmansidneyking1_thumb.jpg?w=244&h=123)

![Gorak_crossRhine1[1] Gorak_crossRhine1[1]](https://lhcizewski.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/gorak_crossrhine11_thumb.jpg?w=244&h=174)